My wife is a Super Mario wizard. She can thread that potbellied mustachioed plumber through the eye of a needle. She mentioned this, in passing, when we started dating—“oh yeah, I used to play a lot of Mario”—but back then neither of us had a console, so I didn’t have a basis for comparison. I mean, lots of people our age played Mario, right?

Not like this.

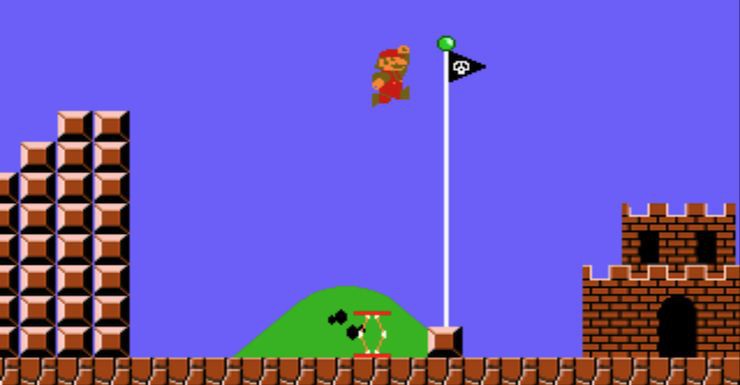

Years ago, a friend downloaded Super Mario for the Wii on a lark. “Check it out! Mario!” Cool, cool. We only had the one controller at the time. Solution: play ’til death, then pass the controller to the right. Until the controller reached my wife.

About three worlds in, I finally picked my jaw off the floor. I don’t have words for most of what I saw. Of course there was an invisible brick just there. How are you running on the ceiling? That fireball totally should have killed you. Wait, how did you get to World Eight?!

You can do that?

My wife had introduced me to the most powerful words in gaming.

Consider Mario—the freedom and surprise of clearing the top of the stage and sliding behind scenery, of finding the other ways to play the game. Or The Stanley Parable’s four way push-and-pull between designer, narrator, character, and player. Or Mass Effect letting you talk bosses into surrender. Or even Saints Row IV’s hour-long rejection of any consistent genre. (Oh! We’re in Call of Duty land. Wait. No. It’s—what? I’m the President?) These surprises kick us out of the rhythm of gaming; they disturb our impression that the right thing to do is keep on keeping on, playing the game the way it’s “meant” to be played.

Something deep in our monkey brainstems blisses out at surprise; a scavenger reflex thrills at the cheap trick. But I like these surprises for a different reason entirely.

You see, it’s easy to forget that we can change the world.

Systems tell stories. “We can’t lose.” “We’re under attack by insidious invaders.” “We’re on the side of the angels.” The trickiest story is the most basic: “It’s always been this way.”

When of course it hasn’t, for good and ill. The US Pledge of Allegiance didn’t contain the words “under God” until the Red Scare. My university didn’t admit women until the late sixties. When I first traveled to China in the early 2000s, most older folk I knew expressed their amazement travel to China was even possible, since it hadn’t been, politically, for most of their lives. Peaceful countries fall apart; enemies become friends; healthy systems decay, and decayed systems reinvent themselves.

Systems project an air of immortality because they need people’s trust to survive. But not all systems deserve to survive unchanged, or unchallenged.

Change starts with vision: the power to see a different world. But it’s not enough to think: “oh, this could be different.” Change requires action, experiment, and trust in possibility. It requires the courage to exercise real freedom.

Which is where games come in. Games give us limits, and the freedom to test them. Sometimes the experiment yields only an error message—but the error message itself is a joy, a sign we’ve pushed to the edge of the world. Game-breaking is a revolutionary act.

When I write prose fiction, I get to set characters interesting challenges. Who killed the judge? Can you save the city and your friends? Should you support this government, or rebel against it? I show characters bucking the rules of their society. But when I write interactive fiction, I can give players the opportunity to surprise themselves. To fight the narrative. To make peace instead of war, or vice versa, and see what happens.

I thought about this stuff a lot as I wrote The City’s Thirst, my new game set in the world of the Craft Sequence novels. You, the player, are a God Wars vet trying to find water for the city of Dresediel Lex—tough job, but you signed up for it when you helped kill the rain god. On its surface, the challenge is straightforward: how do you find the water the city needs to survive? How hard are you willing to fight? Who are you willing to throw under the bus to for the sake of millions?

I thought about this stuff a lot as I wrote The City’s Thirst, my new game set in the world of the Craft Sequence novels. You, the player, are a God Wars vet trying to find water for the city of Dresediel Lex—tough job, but you signed up for it when you helped kill the rain god. On its surface, the challenge is straightforward: how do you find the water the city needs to survive? How hard are you willing to fight? Who are you willing to throw under the bus to for the sake of millions?

That’s the story you’re being told—but maybe it’s not the story you care to tell. The interactive nature of gaming lets me give players room to spin victory into defeat and vice versa, to subvert the structure of the story and set their own goals. If your character thinks the best she can do is work within the confines of an unjust system, she’ll be drawn in that direction. But there are other ways to be. Other worlds to build.

You might not succeed. But at least you can try.

Hell, I might not have succeeded. But if this game offers its players a moment of surprise—if someone sits up and says, “wait, I can do that?”—if I’ve given a shade of that secret-warp jaw drop I get when I watch my wife play Mario, well… I’ll count that as a win.

Max Gladstone writes about the cutthroat world of international necromancy: wizards in pinstriped suits and gods with shareholders’ committees. His new novel, Last First Snow, is about zoning politics, human sacrifice, and parenthood. You can follow him on Twitter.